The Right to Be Forgotten (Google v. Spain)

Summary

In Google v. Spain, the European Court of Justice ruled that the European citizens have a right to request that commercial search firms, such as Google, that gather personal information for profit should remove links to private information when asked, provided the information is no longer relevant. The Court did not say newspapers should remove articles. The Court found that the fundamental right to privacy is greater than the economic interest of the commercial firm and, in some circumstances, the public interest interest in access to Information. The European Court affirmed the judgment of the Spanish Data Protection Agency which upheld press freedoms and rejected a request to have the article concerning personal bankruptcy removed from the web site of the press organization.

EPIC Resources

- 2015 International Consumers, Privacy, and Data Protection Conference, YouTube.

- Marc Rotenberg, Op-Ed, Google's Position Makes No Sense, USA Today, Jan. 22, 2015.

- Marc Rotenberg, The Right To Be Forgotten, The Diane Rehm Show, National Public Radio, Jan. 5, 2015.

- John Tran, Panelist, An Evening Not to be Forgotten, Georgetown University, Oct. 20, 2014.

- Marc Rotenberg, Op-Ed, The Right to Privacy is Global, US News and World Report, Dec. 5, 2014.

- Marc Rotenberg, Op-Ed, EU Strikes Blow for Privacy, USA Today, May 14, 2014.

- Marc Rotenberg, On International Privacy: A Path Forward for the US and Europe, Harvard International Review (Spring 2014).

- Marc Rotenberg & David Jacobs, Updating the Law of Information Privacy: The New Framework of the European Union, 36 Harv. J.L. & Pub. Pol'y, 605 (2013).

From Software Advice's survey:

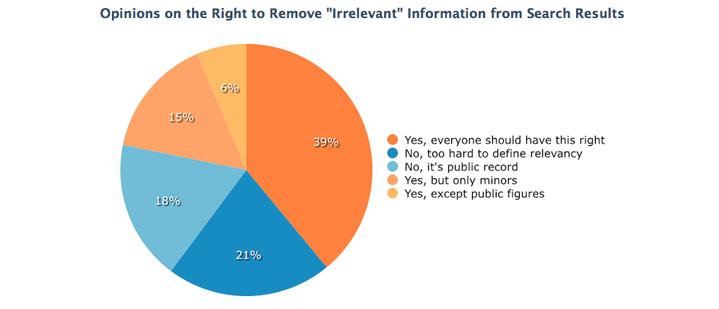

When Europe’s highest court ruled in May that individuals had a “right to be forgotten”—i.e., they have the right to request that outdated or “irrelevant” information about them be removed from search results—the shockwaves were heard around the world.

Given the First Amendment and the traditionally strong emphasis on the public’s right to know in American culture, it may be difficult to imagine such a ruling happening stateside. But American culture is also traditionally strong on protecting privacy—and in fact, in January 2015, variant legislation applicable only to minors will become law in California. What if U.S. citizens start demanding the right to be forgotten, too?

We at Software Advice were intrigued by the possibility, so we surveyed 500 adults in the U.S. to find out how they felt about the right to be forgotten and the problems the law seeks to address. We then quizzed a panel of experts for their opinions on this complex issue.

Key Findings:

Sixty-one percent of Americans believe some version of the right to be forgotten is necessary.

Thirty-nine percent want a European-style blanket right to be forgotten, without restrictions.

Nearly half of respondents were concerned that "irrelevant" search results can harm a person’s reputation.

Top News

- Pew Survey: Americans Support 'Right to Be Forgotten': A new Pew Research survey found that 74% of U.S. adults say it is more important to keep things about themselves from being searchable online than it is to discover potentially useful information about others. And 85% say that all Americans should have the right to have potentially embarrassing photos and videos removed from online search results. EPIC advocates for the "right to be forgotten" and maintains a webpage on U.S. state laws that allow individuals to remove records containing disparaging information. EPIC publication "The Right to be Forgotten on the Internet: Google v. Spain," an account of the original case written by former Spanish Privacy Commissioner Artemi Rallo, is available in the EPIC bookstore. (Jan. 27, 2020)

- Google Wins Global Delisting Case at European High Court, But Paragraph 72: In Google v. CNIL, the Court of Justice for the European Union ruled Google is not required to apply Europeans' requests to de-reference search results globally. The case follows an earlier ruling in Google v. Spain that Europeans have a right to remove links to their personal data in Google search results - the "Right to Be Forgotten." In the most recent case, the Court ruled that "currently there is no obligation under EU law, for a search engine operator...to carry out such a de-referencing on all the versions of its search engine." However, the Court also said that the search operator must "take sufficiently effective measures" to prevent searches for deferenced information from within the EU with a search engine outside of the EU. The Court also stated, in paragraph 72, that national authorities, in some circumstances, could require global delisting. EPIC supported the CNIL's approach contending that "commercial search firms should remove links to private information when asked." EPIC published "The Right to be Forgotten on the Internet: Google v. Spain" an account of the original case by former Spanish Privacy Commissioner Artemi Rallo. (Sep. 25, 2019) More top news »

Background

Procedural History

In 2010 Mario Costeja González, filed a complaint with the Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEDP), the Spanish Data Protection Agency, against a local newspaper and Google Spain for claims relating to auction notices mentioning González published in 1998. The notices concerned real estate auctions held to secure repayment of González's social security debts. González contended that these pages were no longer necessary because "the attachment proceedings concerning him had been fully resolved for a number of years and that reference to them was now entirely irrelevant." He sought to have the local newspaper, La Vanguardia, remove the pages or alter them so his personal information was no longer displayed. He also sought for Google Inc. to remove the links to the articles in question so that the information no longer appeared in Google Search results.

The AEDP dismissed the plaintiff's claims against the newspaper, but allowed those against Google. Google appealed to Spain's high court, which in turn referred three questions to the ECJ:

(1) Whether EU rules apply to search engines if they have a branch or subsidiary in a Member State;

(2) Whether the Directive applies to search engines; and

(3) Whether an individual has the right to request that their personal data be removed from search results (i.e. the "right to be forgotten").

ECJ Decision

The ECJ first ruled that the Directive applies to search engines. The Directive sets forth rules for "controllers" involved in the "processing of personal data." The ECJ held that search engines engage in "processing of data" because they explore the internet "automatically, constantly and systematically in search of the information." The ECJ further held that search engines are "controllers" within the meaning of the Directive because search engines "determine[] the purposes and means of" data processing.

Second, the Court concluded that because Google Inc. had a subsidiary (Google Spain) operating within the territory of Spain (a Member State), even though Google itself is based within a non-member state (the United States), the directive properly applied to Google and Google operated as "an 'establishment' within the meaning of the directive." The Court concluded this despite Google's assertion that the data was not processed within Spain, because Google intended to "promote and sell, in the Member State in question, advertising space offered by the search engine in order to make the service offered by the engine profitable." For these reasons, ruled the Court, Google has an obligation in certain cases to remove the links to pages displayed by third parties, even if the information published by those third parties is itself lawful.

Third, the ECJ held that individuals have a right to request search engines to remove links to personal information. The Court held Article 12(b) of the Directive gives individuals the right to ask search engine operators to erase search results that are incompatible with Article 6. Article 12(b) of the Directive give data subjects the right to "rectification, erasure or blocking of data the processing of which does not comply with the provisions of [the] Directive." Article 6 requires that data is "adequate, relevant and not excessive in relation to the purposes for which they are collected", "accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date", and "kept in a form which permits identification of data subjects for no longer than necessary." The Court also made clear that it is not necessary to find that links cause prejudice to the data subject. The Court held that "a fair balance should be sought in particular between that interest and the data subject's fundamental rights." However, "those rights override, as a rule, not only the economic interest of the operator of a search engine but also the interest of the general public in finding that information . . . ." This balance would vary on a case-by-case basis and may depend on "the nature of the information in question and its sensitivity for the data subject's private life" and the public's interest in the information. The public's interest, in turn, may vary depending on whether the individual is a public figure. According to the Court, Google's economic interest and the public's interest in links to Gonzalez's auction notices did not outweigh the serious interference with Gonzalez's fundamental rights under the Directive.

Legal Documents

- Art. 29 Working Party Implementation Guidelines (Nov. 2, 2014)

- Judgement of the Court (May 13, 2014)

- EU Press Release Describing the Decision (May 13, 2014)

- EU Data Protection Directive (1995)

- Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2009)

Additional Resources

- Marc Rotenberg, Google, Europe and Privacy, New York Times (May 2, 2016)

- Intelligence Squared Debate: The U.S. Should Adopt the "Right to Be Forgotten" Online, Mar. 11, 2015.

- Cambridge Code (Academic Commentary: Google Spain)

- Google Transparency Report: European Privacy Requests for Search Removals (last updated Nov. 17, 2014).

- European Commission, Factsheet on the "Right to be Forgotten" ruling (2012).

- Commission Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council, Art. 4(2), COM (2012) 11 final (Jan. 25, 2012), Proposed Data Protection Regulation.

- Viviane Reding, The EU Data protection Reform 2012: Making Europe the Standard Setter for Modern Data Protection Rules in the Digital Age, January 22, 2012, Speech in Munich, Germany before the Innovation Conference Digital, Life, Design.

- Jeffrey Rosen, The Right to Be Forgotten 64 Stan. L. Rev. Online 88, February 13, 2012.

- Steven C. Bennett, The "Right to Be Forgotten": Reconciling EU and US Perspectives Berkley J. Int'L Law 161 (2012).

- Meg Ambrose and Jef Ausloos, The Right to be Forgotten Across the Pond, 3 Journal of Information Policy 1 (2012).

EPIC's Related Work

- Expungement

-

The social consequences of a criminal record can lead to the denial of an individual's right to civic participation. Life, subsequent to an arrest, is permanently altered. Regardless of whether an individual has been convicted, an arrest or citation typically persists on a criminal record. Therefore, even a person who has had the charges against them dropped may be subject to a degree of social ostracism and a de facto public finding of guilt. Some states permit individuals who are arrested, but not convicted, to expunge their arrest records. Others permit some convicts to apply for expungements after time has passed from the completion of their sentences.

- G.D. v. Kenny

-

In G.D. v. Kenny, a case raising both defamation and privacy tort claims, the Supreme Court of New Jersey has held that defendants are entitled to assert truth as a defense, even when the relevant facts are subject to an expungement order under a state statute. The Court relied on the fact that criminal conviction information is disseminated before the entry of an expungement judgement. In an amicus brief, EPIC had urged the New Jersey Supreme Court to preserve the value of expungement and further argued that data broker firms will make available inaccurate and incomplete information if expungement orders are not enforced by the state. The case may have implications for the "Right to be Forgotten."

News

- Kelly Fiveash, Google Extends Right-to-be-Forgotten Rules to All Search Sites, ArsTechnica (Mar. 7, 2016).

- Liza Tucker, Op-Ed, The Right to Bury the (Online) Past, Wash. Post, Sept. 13, 2015.

- Zoya Sheftalovich, Google ordered to remove UK search results, Politico EU, August 21, 2015

- Sylvia Tippman and Julia Powles, Google Accidentally Reveals Data on 'Right to Be Forgotten' Requests, The Guardian, July 14, 2014.

- Mark Scott, France Wants Google to Apply ‘Right to Be Forgotten’ Ruling Worldwide or Face Penalties, NY Times, June 12, 2015

- Mario Trujillo, Public Wants "Right to Be Forgotten" Online, The Hill, Mar. 19, 2015

- Daniel Wilson, FTC's Brill Backs Enhanced Consumer 'Right To Obscurity', Law360, Mar. 10, 2015. More news »

Share this page:

Subscribe to the EPIC Alert

The EPIC Alert is a biweekly newsletter highlighting emerging privacy issues.