Rules and Regulations Implementing the Telephone Consumer Protection Act

of 1991

Docket Nos. CG 02-278, DA 05-2975 ��

Comments of the Electronic Privacy Information Center

January 13, 2006

Pursuant to the notice published by the Federal Communications Commission (Commission) on December 14, 2005 seeking comments on a petition for declaratory ruling filed by the Fax Ban Coalition, the Electronic Privacy Information Center submit the following comments.[1]

I. �������� Introduction

The Commission should deny the Petitioner's request to preempt California's and other states' heightened protections against junk faxes.� California established an opt-in, or affirmative consent requirement before junk faxes are sent to balance the interest of facsimile machine owners against the senders who inundate machines with unsolicited advertising.� Junk faxes waste resources and annoy owners of fax machines.� Many who have purchased fax machines turn the fax function off, after being repeatedly called by junk faxers in the middle of the night.� Junk faxes are of such annoyance that the California protections (labeled as "particularly egregious" by Petitioner) sailed through the State's Democrat-dominated Senate and Assembly and were signed by a Republican Governor.

Petitioners have not met the burden of showing that Congress acted with a "clear and manifest purpose"[2] to preempt state laws.� In fact, Congress had no such intent in passing the TCPA.� Instead, Congress has repeatedly passed up the opportunity to explicitly preempt state anti-telemarketing laws, setting a uniform floor of protections that all Americans enjoy, which may be supplemented by stronger state laws.

California's heightened protections against junk faxes constitute a democratic attempt to rein in an advertising practice that sometimes employs channels of interstate communication.� These heightened protections pose no technical burdens to communications networks.� They do not specify new protocols or other rules that hamper actual communication.� Instead, they regulate a common, obnoxious business practice.� Taken literally, Petitioner's argument would mean that states would have no power to address abusive marketing practices, so long as they employ interstate channels of communication.� Such an interpretation would give scammers an enormous safe haven from state consumer protection laws.�

Like other state anti-telemarketing laws, heightened junk fax prohibitions serve the historic state police power to protect individuals from abusive calling practices.� These laws represent innovation in addressing quickly-evolving business practices and recognize regional needs that may not rise to the attention of federal regulators.�

Americans owe the highly successful Telemarketing Do-Not-Call Registry to such state innovation.� The Do-Not-Call Registry is just one example of many consumer privacy protections developed by state legislatures that are later adopted at the federal level by Congress or an administrative agency.� Consumers will continue to be served best by a dual regulation system that allows state responses to marketing practices.

Overall, the Petitioner conflates Congress' interest in providing blanket protection against telemarketing practices for all Americans with the idea that there needs to be a ceiling of uniform standards.� That is, the Petitioner sees uniformity as an end in itself, rather than the attempt by Congress to ensure that individuals in all 50 states have some form of protection against telemarketing abuses.� The difference is that Congress acted to enhance individuals' rights--to ensure that everyone has some shield against telemarketing and fax marketing.� The Petitioner wants to use the TCPA to reduce individuals' rights, to convert the TCPA into a license for unwanted junk faxing.� Petitioner seeks to use "uniformity" as a means to flatten state laws, rather than recognizing that uniformity in the context of the TCPA was an attempt to ensure that everyone should have a floor of protections against unwanted solicitation.

Here, the Petitioner seeks to undo years of democratic processes with a 20-page petition that omits the basic legal test established to determine whether Congress intended to supercede state regulation.� Petitioner attempts to find preemption by bootstrapping language from other statutes.� Bootstrapping cannot demonstrate a "clear and manifest" purpose to preempt.� We therefore urge the Commission to deny Petitioner's attempt to erase hundreds of consumer protection statutes.� We urge the Commission to find that the TCPA anticipates and accommodates supplemental state protections against the scourge of unwanted telemarketing and junk fax marketing.

II. ������ In Passing the TCPA, Congress Did Not Demonstrate an Intent to Preempt State Laws

A.������� In order to supercede the state laws at issue, Petitioners must demonstrate a "clear and manifest" intent by Congress to preempt state laws�

��������������� Petitioners have not met the burden of establishing a "clear and manifest" congressional intent to preempt state anti-telemarketing laws.� While Congress may preempt state law either explicitly or implicitly, it has done neither in the TCPA.� ��

1. �������� State regulation of interstate telemarketing is not expressly preempted by the TCPA

The TCPA does not expressly preempt state anti-telemarketing laws.� It is silent on preemption of interstate telemarketing, and specifically preserves intrastate telemarketing.� Because the statute does not contain clear language preventing states from regulating interstate telemarketing calls, state regulation of such calls is not explicitly preempted.�

2. �������� State regulation of interstate telemarketing is not implicitly preempted by the TCPA

While Congress may also preempt state law implicitly, it has not done so in the TCPA.� The Court has held that

[i]n the absence of an express statement by Congress that state law is pre-empted, there are two other bases for finding pre-emption.� First, when Congress intends that a federal law occupy a given field, state law in that field is pre-empted.� Second, even if Congress has not occupied the field, state law is nevertheless pre-empted to the extent it actually conflicts with federal law, that is, when compliance with both state and federal law is impossible, or when the state law stands as an obstacle to the accomplishment and execution of the full purposes and objectives of Congress.[3]�

Neither of these forms of preemption, "field" or "floor" (also referred to as "conflict"), justifies invalidation of the state anti-telemarketing laws at issue.

a. �������� Congress did not intend to prohibit the states from regulating in the field of telemarketing

����������� By enacting the TCPA, Congress did not intend to prohibit state regulation in the field of telemarketing.� To determine whether Congress has preempted the states from regulating within the field covered by the legislation, "[t]he [] inquiry is whether Congress, pursuant to its power to regulate commerce � has prohibited state regulation of the particular aspects of commerce involved in [the] case."� If the field that Congress is said to have preempted is one that has traditionally been occupied by the states, it is presumed that "the historic police powers of the States were not to be superceded by the Federal Act unless that was the clear and manifest purpose of Congress."[4]�

����������� Petitioners erroneously contend that the Commission has exclusive authority over interstate telemarketing.� Petitioners start from the premise that the Communications Act of 1934 granted the Commission jurisdiction over "all interstate and foreign communication ."[5]�� Though the Commission has jurisdiction over all interstate communication, it does not follow that the Commission has jurisdiction over all interstate telemarketing.� Telemarketing cannot be classified as communication alone; there is an overwhelming element of advertising or solicitation.� The telephone is merely a vehicle for delivering advertising to consumers.� Because businesses use the telephone to solicit sales, the interest in consumer protection, an interest long protected by the states, is triggered.�

Because telemarketing implicates consumer protection, an area long regulated by the states,[6] the Commission must begin with the assumption that state laws regulating telemarketing were not to be preempted, unless Congress clearly intended preemption.[7]� There is no evidence of congressional intent to prohibit state laws regulating telemarketing.� In fact, the evidence is just the opposite.� Congress explicitly allowed the states to regulate intrastate telemarketing, providing that "nothing � shall preempt any State law that imposes more restrictive intrastate requirements or regulations�"[8]� Congress was silent on interstate regulations, and easily could have inserted a single sentence in the TCPA or Junk Fax Prevention Act if it had intended to supercede state laws.���������

The dicta relied upon by the Petitioner does not support a finding of preemption with respect to the TCPA.� In the first case cited by the Petitioner, the Supreme Court held that federal law did not preempt state laws concerning depreciation of property owned by carriers.[9]� Additionally, in National Asso. of Regulatory Utility Comm'rs v. FCC, the court preempted a state regulation, but in that case, the regulation adversely affected federal goals in providing a "rapid, efficient, Nation-wide . . . communication service."[10]� Nothing about the junk fax regulations established in California and other states impedes the rapidity of signals or their efficiency.� California's heightened junk fax regulation only limits an obnoxious and illegitimate business practice, not the technical delivery of communications services.�

b. In enacting the TCPA, Congress intended floor, not ceiling, preemption, thus permitting states to enact stronger regulations

Congress intended the TCPA to act as a floor, rather than a ceiling.� This approach permits states to enact stronger telemarketing regulations than exist at the federal level.� As the Court has held,

even if Congress has not occupied the field, state law is nevertheless pre-empted to the extent it actually conflicts with federal law, that is, when compliance with both state and federal law is impossible, or when the state law stands as an obstacle to the accomplishment and execution of the full purposes and objectives of Congress.[11]

This is known as "floor" preemption � federal law acts as a floor of protections that can be enhanced by more stringent state laws.�

Congressional intent is the critical factor in preemption analysis.[12]� In interpreting a preemption clause, a court "must give effect to [its] plain language unless there is good reason to believe Congress intended the language to have some more restrictive meaning."[13]� Though Congress did not explicitly state a purpose or an objective in the TCPA, a number of congressional findings led to the passage of and were included in the TCPA.� Congress found:

(5) Unrestricted telemarketing � can be an intrusive invasion of privacy �

�

(7) Over half the States now have statutes restricting various uses of the telephone for marketing, but telemarketers can evade their prohibitions through interstate operations; therefore, Federal law is needed to control residential telemarketing practices.

�

(9) Individuals' privacy rights, public safety interests, and commercial freedoms of speech and trade must be balanced in a way that protects the privacy of individuals and permits legitimate telemarketing practices.

(10) Evidence compiled by the Congress indicates that residential telephone subscribers consider automated or prerecorded telephone calls, regardless of the content or the initiator of the message, to be a nuisance and an invasion of privacy.

�

(12) Banning such automated or prerecorded telephone calls to the home, except when the receiving party consents to receiving the call or when such calls are necessary in an emergency situation affecting the health and safety of the consumer, is the only effective means of protecting telephone consumers from this nuisance and privacy invasion.[14]

Congress' findings clearly emphasize the need to protect consumers from invasions of their privacy.� Because the TCPA was passed to address this significant need, protecting consumers' privacy was the clear purpose of the statute.� Nowhere in the findings does Congress recognize the need to create "uniform national standards" or the like.�

Petitioners' assertion that Congress' principal objective in enacting the TCPA was "to provide a uniform workable framework" is erroneous.� First, Congress demonstrated no intent to establish uniform standards.� The word "uniform" does not appear either in the congressional findings or the text of the TCPA.� The word "national" appears only as related to the permission granted to the Commission to establish a national Do-Not-Call Registry.� Second, Congress was less concerned about the practices of telemarketers than it was about the privacy interests of consumers.� In only one of fifteen findings does Congress mention the need to "permit legitimate telemarketing practices."[15]� In contrast, Congress emphasizes the need to protect consumers' right to privacy in nine of the findings.[16]

Courts in several jurisdictions have concluded that the purpose of the TCPA was to protect consumer privacy.[17]� In addition, the Eighth Circuit has confirmed the lack of congressional intent to preempt state laws.� In Van Bergen v. State of Minnesota,[18] the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals decidedly ruled out preemption of state law under the TCPA.� It emphasized, "If Congress intended to preempt other state laws, that intent could easily have been expressed as part of the same provision."[19]�� This is especially persuasive as at least eight states had anti-telemarketing laws at the time the TCPA was enacted.[20]� Congress, being aware of the existence state anti-telemarketing laws, would have preempted such laws if that had been its intent.� Further, if Congress had intended to create a "uniform" regulatory scheme, it would not have expressly precluded preemption of state regulation in one area of telemarketing � intrastate telemarketing.

Because state laws regulating interstate telemarketing and the TCPA share

the same purpose � protecting consumers from an invasion of privacy � the

state laws do not stand as obstacles to the accomplishment of congressional

objectives.

B.�������� Petitioners cannot overcome the strong legal presumption against preemption of state law����������������������������������������������������

1. �������� Petitioners have not overcome the strong legal presumption against preemption of state law

����������� The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized the strong legal presumption against preemption of state law. �Because petitioners have not been able to rebut this presumption, the Commission should not invalidate the state laws at issue.[21]� The Supreme Court has cited "the oft-repeated rule that the State, in the absence of express action by Congress, may regulate many matters which indirectly affect interstate commerce, but which are for the comfort and convenience of its citizens."[22]� The Court has further stated that "[o]f the existence of such a rule there can be no question.� It is settled and illustrated by many cases."[23]� In addition, the Court has emphasized that "interstate commerce in its practical conduct has many incidents having varying degrees of connection with it and effect upon it over which the State may have some power."[24]

2. �������� The presumption against preemption is especially strong in this case, because Petitioners seek to invalidate laws related to the historical state police power

The presumption against preemption of state law is especially strong as related to the state police power, an area traditionally regulated by the states.[25]� The Supreme Court has held that where "the field which Congress is said to have pre-empted has been traditionally occupied by the states, we start with the assumption that the historic police powers of the States were not to be superseded by the Federal Act unless that was the clear and manifest purpose of Congress."[26]� Consumer protection is part of the state police power,[27] and thus it enjoys the heightened presumption against preemption of state law.� The Court has stated, "Given the long history of state common-law and statutory remedies against monopolies and unfair business practices, it is plain that this is an area traditionally regulated by the States."[28]

C.������� The Commission must interpret the TCPA in a reasonable manner; it is unreasonable to read ceiling preemption into the TCPA

The Commission must interpret the TCPA in a reasonable manner.� The Commission's interpretation of the statute is governed by Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council.[29]� Under Chevron, if Congress' intent is clear from the statute, the Commission must follow the expressed intent of Congress.� If, however, the statute is silent or ambiguous with respect to the issue at hand, the agency must interpret the statute in a reasonable manner.� As discussed above, at best the TCPA preemption provision is ambiguous as to whether state regulation of interstate telemarketing is permitted.�

The Commission itself has acknowledged that the preemption provision of the TCPA is ambiguous as to whether the Commission is prohibited from preempting state laws that regulate both intrastate and interstate calls.[30]� Further, the Commission has indicated that the provision is silent on the issue of whether a state law that imposes more restrictive regulations on interstate telemarketing calls may be preempted.[31]� The Commission has nevertheless indicated that "more restrictive efforts to regulate interstate calling would almost certainly conflict with [its] rules."[32]� However, the primary justification given for this assertion is that the Commission believes it was the "clear intent" of Congress to "promote a uniform regulatory scheme under which telemarketers would not be subject to multiple, conflicting regulations."[33]� Again, there is no mention of such a scheme in the text of the TCPA, nor does the statute even use the word "uniform."�

The authority cited by the Commission for this "clear intent" is a single remark of one member of Congress, Senator Larry Pressler, on the floor of the Senate.[34]� However, read in context, the statement made by Senator Pressler during discussion of the TCPA � "The Federal Government needs to act now on uniform legislation to protect consumers" � merely summarizes the message of the testimony that was received by the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee on S. 1410, an anti-telemarketing bill introduced by Pressler.[35]� Further, Pressler's next comments were, "The primary purpose of [the TCPA] is to develop the necessary ground rules for cost-effective protection of consumers from unwanted telephone solicitations."[36]� The emphasis of Senator Pressler's remarks is clearly on the protection of consumers' privacy rights.� Pressler makes no further comment on what "uniform legislation" would entail, and whether the notion even relates to the balance of power between the Commission and the states.�

Others have proposed that any call for uniformity does not relate to the jurisdiction of federal and state governments, but instead relates to a congressional mandate that the Commission and another federal agency, the Federal Trade Commission, coordinate their efforts and design one federal Do-Not-Call Registry.� The Commission's assertion of Congress' interest in "uniformity" is not supported by the legislative history of the TCPA.� Basing this assertion on the remarks of a single Senator is not persuasive; reading the remarks in context reveals that this authority is even less persuasive.

Furthermore, in the Commission's own interpretation of the TCPA, the Commission has indicated that the objective of the TCPA is "to address a growing number of telephone marketing calls and certain telemarketing practices thought to be an invasion of consumer privacy and even a risk to public safety."[37]

The Commission may act only as authorized by Congress, and it must interpret

Congress' actions in a reasonable manner.� It would be unreasonable and

outside the Commission's authority to read into the TCPA a broad intent

to preempt state law.

III.����� State Laws Regulating Interstate Telemarketing and Fax Marketing Calls Should Not be Preempted by Federal Law

����������� Not only are state anti-telemarketing and junk fax laws not legally prohibited by the TCPA, as a policy matter, such laws should not be preempted.

A.�������� Telemarketing companies are deliberately and knowingly targeting out-of-state residents

Telemarketers are both deliberately and knowingly using marketing techniques that target out-of-state residents.� In targeting residents of other states, they must comply with consumer protection laws in the call recipient's state.

Telemarketers should be held to the same standards that apply to other direct marketers.� When a company engages in other forms of direct marketing, such as catalog sales, it is required to comply with all applicable state laws, including differing state sales taxes, product labeling requirements, and product bans.� Telemarketers should have to comply in similar ways.

B.�������� Consumers are best served when both state and federal officials can work to protect them against unlawful business practices

Consumers are best protected against unlawful business practices by a combination of federal and state laws.� The federal government simply cannot accommodate the diverse interests and needs that are served by state consumer protection laws.� For instance, in July 2005, DMNews[38] reported on a telemarketing ban implemented by Louisiana in response to a storm.[39]� In that State, an emergency powers law permits the government to temporarily suspend telemarketing operations during an emergency.� This type of state response to a public emergency cannot practicably be performed by the federal government.� The value of state law and the limits of federal power to respond to such emergencies is clear.

C.������� The traditional role of the states in regulating privacy should be preserved

States have a traditional role in regulating privacy that should be preserved.� There is a presumption in American law that state and local governments are primarily responsible for matters of health and safety.[40]� Privacy is included in the category of health and safety issues, as an area of regulation historically left to the states.[41]� Further, the Commission has recognized that "states have a long history of regulating telemarketing practices."[42]

D.������� Historically, most privacy law allows states to provide greater protections

Federal consumer protection and privacy laws, as a general matter, operate as regulatory baselines and do not prevent states from enacting and enforcing stronger state statutes.� The Electronic Communications Privacy Act,[43]the Right to Financial Privacy Act,[44] the Cable Communications Privacy Act,[45] the Video Privacy Protection Act,[46] the Employee Polygraph Protection Act,[47] the Driver's Privacy Protection Act,[48] the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act,[49] the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act,[50] and portions of the Fair Credit Reporting Act[51] all allow states to craft protections that exceed federal law.� In each of the areas regulated by the above-referenced privacy laws, business has continued to flourish in states that have enacted stronger privacy protections.�

E.�������� Permitting state laws promotes regulatory innovation and experimentation

Permitting the states to regulate interstate telemarketing and junk faxing will continue to promote regulatory innovation and experimentation.� As Justice Brandeis once remarked, "It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country."[52]� States enjoy a unique perspective that allows them to craft innovative programs to protect consumers.� State legislators are closer to their constituents and the entities they regulate.� They are the first to see trends and problems, and are well-suited to address new challenges and opportunities that arise from evolving technologies and business practices.� State-level policy experimentation fosters the development of best practices.�

�An entire appendix to the 1977 report of the Privacy Protection Study Commission[53] entitled Personal Privacy in an Information Society[54] was devoted to "Privacy Law in the States." This portion of the report speaks strongly to the value of state privacy protection:

Through constitutional, statutory, and common law protections, and through independent studies, the 50 States have taken steps to protect the privacy interests of individuals in many different types of records that others maintain about them.� More often than not, actions taken by State legislatures, and by State courts, have been more innovative and far reaching than similar actions at the Federal level � the states have also shown an acute appreciation of the need to balance privacy interests against other social values.[55]�

The report emphasized "the central role the States can play as protectors of personal privacy, and more broadly, individual liberty": "The States have demonstrated that they can, and do, provide conditions for experiments that preserve and enhance the interests of the individual in our technological, information-dependent society."

State laws are often later adopted at the federal level.� Indeed, states have taken the lead in developing and enforcing legislative safeguards for consumer protection and privacy.� At least thirty-six states had passed do-not-call statutes prior to implementation of the federal Do-Not-Call Registry in 2003.[56] The Joint Petitioners' proposal is contrary to the core principles of our federalist system.� Preemption of state anti-telemarketing laws would inhibit the development of best practices by individual states and significantly undermine the country's traditional structure of consumer protection.

F.�������� State legislators and law enforcers are more accountable to the public interest

State and local governments are more accountable than the federal government to their constituents.� As a result, it is likely that stronger protections will emerge from state and local legislatures, and more vigorous enforcement will be pursued by state actors.� In addition, the Commission has limited resources for enforcement; states should share this responsibility.� In the context of telemarketing, the Commission has stated that "it is critical to combine the resources and expertise of the state and federal governments to ensure compliance with the national do-not-call rules."[57]� With limited enforcement, consumer protection and privacy laws will have little effect.

G.������� Businesses are not put at a particular disadvantage by having to comply with differing state junk fax laws

Telemarketing companies are not put at a disadvantage by having to comply with differing state laws.� Especially in the financial services and credit reporting areas, many businesses have argued that a national ceiling of laws is needed in order to prevent "balkanization" or a "patchwork" of state laws.� As the National Association of Attorneys General Privacy Subcommittee has observed,

Many businesses � argue the importance of a single, federal standard by citing the need for uniformity.� They assert that a 'patchwork' of state laws will make compliance costly and may stifle the development of markets both on and offline.� In fact, businesses have long accommodated themselves to a range of state consumer protection statutes while maintaining a profitable enterprise.� Courts have, for years, engaged in a process of reconciling potentially or actually conflicting laws through application of established legal principles to various factual situations.� Such a tailored response is especially appropriate with respect to evolving technologies and new applications of those technologies.� This flexible approach accommodates the needs of both businesses and consumers, while preserving state sovereignty in an area where states have traditionally had a significant role.[58]

There is nothing that differentiates businesses that engage in telemarketing from other industries that operate at the national level with varying state laws.� For instance, the insurance industry is not regulated at the federal level and is subject to varying legal requirements in the states.� Yet the insurance industry has thrived under this system of regulation.�

Further, any marketing barriers created by state laws apply equally to those with and without an existing business relationship with registered telephone subscribers.� Just because a consumer has purchased goods or services from a business in the past, does not mean that the consumer wishes to hear from that business again through junk faxes.� In addition, there are many other means for businesses to contact customers with whom they have an established relationship, including direct mail and in-store displays.[59]� The benefit to a consumer of not receiving junk faxes calls far outweighs the cost to businesses that would like to engage in such telemarketing.� Petitioners have not demonstrated that state junk fax laws have been an inconvenience the legitimate operations of the direct marketing industry.

H.������� Modern profiling technology demonstrates that compliance with the laws of multiple jurisdictions is possible

1. ��������� Petitioners have not demonstrated that the dual federal-state regulatory system, which has worked successfully for almost fifteen years, is in need of change

Petitioners have not successfully made the case that preemption is now needed.� Though Petitioners argue that compliance with differing state laws are too burdensome, they have lived under this dual federal-state regulatory system for almost fifteen years.� If this system were really so burdensome, the telemarketing industry would have, and should have, objected to the system long ago.� The Petitioners' arguments, viewed in context of almost fifteen years of compliance with varying state laws, appear to be motivated more by political opportunity than technical or legal impossibility.

2. �������� New technologies make compliance with state laws easier now than in any time in history

New technologies make it easier for telemarketers today to comply with differing state laws.� Interstate commerce did not begin with the Internet.� Businesses have long had to comply with varying state laws as a condition of doing business within a state.� And today, with sophisticated location technology and consumer profiling, the direct marketing industry is better equipped than ever to comply with varying state laws.� The need for ceiling uniformity is an overvalued idea that does not account for the industry's ability to treat different people differently � at least when there is a profit motive involved.

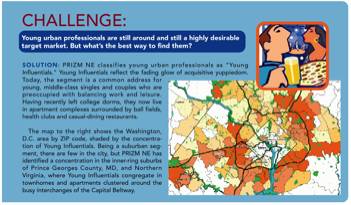

����������� The same technologies that have enabled customer profiling and segmentation could enable compliance with different state laws.� Direct marketers speak breathlessly about their ability to "segment" the public, that is, to treat different people differently.� These companies will go to great lengths to divide people into different groups and pitch varying advertising messages to them.� For instance, commercial data broker Acxiom released a new customer profiling system in June 2005.� As it was described: "Personicx ANSWERS gives users more immediate access to data for marketing planning and analysis.� Personicx places each U.S. household in one of 70 segments, or clusters, and 21 life-stage groups based on behavior and demographic characteristics."[60]� In addition, Claritas' PRIZM system has been used to profile American consumers for decades, and currently consists of a "62-cluster version of PRIZM and the 95-atom MicroVision system at the ZIP+4 level."[61]� These two companies categorize individuals on issues much more nuanced than the state in which they live � these categories concern lifestyle, income, and personal attitudes.

Direct marketers' own advertising literature shows that the industry can even categorize people at the zip code level.� In a brochure discussing the segmentation ability of data broker Claritas, the company demonstrates how it can easily identify "young urban professionals" across three jurisdictions.[62]� The brochure shows an analysis performed at the zip code level of "Young Influentials," a group that reflects "the fading glow of acquisitive yuppiedom."

Claritas' systems can locate yuppie "concentration[s] in the inner-ring suburbs of Prince Georges County, MD, and Northern Virginia."� If Claritas can discriminate on this level based on so many factors, direct marketers should be called upon to explain why this same technology cannot enable compliance with state law.[63]�

From a technical perspective, coding in different time of call, established business relationship, or permission to continue laws is trivial.� Markers can be placed in the database to highlight individuals who reside in states with stricter junk fax laws, and telemarketers could be instructed not to initiate messages, or to send these individuals messages at specific times or in compliance with specific rules.

The Commission should view claims for a need for uniformity with much greater skepticism.� New tools make it easier now than ever to treat people differently.� The industry should have to bear the burden of explaining how on one hand it can give different people who live on the same block different credit card offers, but it cannot treat people who live in different states differently when it comes to telemarketing regulations.

I.��������� State residents support state telemarketing laws

����������� Many state legislatures have determined that their residents have a strong interest in privacy and have consequently promulgated laws regulating telemarketing and junk faxing.� These states have adopted legislation that preserves the right of those who want to receive telemarketing calls to do so, while safeguarding the privacy interests of those consumers who are not interested in receiving such calls.� Joint Petitioners now seek to eviscerate these statutory safeguards and to substitute their own judgment about who should receive telemarketing calls.

����������� State residents have grown accustomed to the protections offered by their respective states.� Many residents oppose imposition of an existing business relationship exemption.[64]� Requiring states to follow the federal model, which includes allowing telemarketing calls to existing customers, would eliminate the residential peace that state residents have come to enjoy.� Such a requirement would contravene the overall goal of the Commission's Do-Not-Call Registry � protecting consumers from the invasion of privacy resulting from telemarketing calls.

IV. ����� Conclusion

����������� Based on the foregoing, the Commission should expressly declare that the TCPA does not preempt state laws regulating junk faxing.

Respectfully Submitted,

/s

Chris Jay Hoofnagle

Attorney for the Electronic Privacy Information Center

West Coast Office

944 Market St. #709

San Francisco, CA 94102

415-981-6400

January 13, 2006

[1]� Rules and Regulations Implementing the Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991, 70 Fed. Reg. 74014 (Dec. 14, 2005).

[2] See Jones v. Rath Packing Co., 430 U.S. 519, 525 (1977) (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 U.S. 218, 230 (1947)).

[3] Cal. v. ARC America Corp., 490 U.S. 93, 100-01 (1989) (internal quotation marks and citations omitted) (citing Pacific Gas & Elec. Co. v. State Energy Res. Conservation and Dev. Comm'n, 461 U.S. 190, 212-13 (1983) and Florida Lime & Avocado Growers, Inc. v. Paul, 373 U.S. 132, 142-43 (1963), quoting Hines v. Davidowitz, 312 U.S. 52, 67 (1941)).

[4] Rath Packing Co., 430 U.S. at 525 (internal quotations omitted) (quoting Rice, 331 U.S. at 230).

[5] Communications Act of 1934, 47 U.S.C. � 152(a) (2005).

[6] ARC America Corp., 490 U.S. at 101.

[7] Rath Packing Co., 430 U.S. at 525 (quoting Rice,331 U.S. at 230).

[8] Telephone Consumer Protection Act, 47 U.S.C. � 227(e)(1) (2005).

[9] La. Public Serv. Com v. FCC, 476 U.S. 355 (1986).

[10]241 U.S. App. D.C. 175 (D.C. Cir. 1984).

[11] Cal v. ARC America Corp., 490 U.S. 93, 100-01 (1947) (internal quotation marks and citations omitted) (citing Pacific Gas & Elec. Co. v. State Energy Res. Conservation and Dev. Comm'n, 461 U.S. 190, 212-13 (1983) and Florida Lime & Avocado Growers, Inc. v. Paul, 373 U.S. 132, 142-43 (1963), quoting Hines v. Davidowitz, 312 U.S. 52, 67 (1941)).

[12] Cipollone v. Liggett Group, Inc., 505 U.S. 504, 516; see also Am. Bankers Ass'n v. Gould, 2005 U.S. App. LEXIS 11760 at *11 (9th Cir. June 20, 2005).

[13] Shaw v. Delta Air Lines, Inc., 463 U.S. 85, 97 (1983); see also Gould, 2005 U.S. App. LEXIS 11760 at *10-11 (9th Cir. June 20, 2005).

[14] Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991, Pub. L. No. 102-243, �2, 105 Stat. 2394.

[15] Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991, Pub. L. No. 102-243, �2(9), 105 Stat. 2394.

[16] Id. at � 2(5)-(7), (9)-(14).

[17] See, e.g., Int'l Sci. & Tech. Inst. v. Inacom Commc'ns, Inc., 106 F.2d 1146, 1150 (4th Cir. 1997); Park Univ. Enters. v. Am. Cas. Co. of Reading, Pa., 314 F. Supp. 2d 1094, 1109 (D.Kan. 2004); Registry Dallas Assocs. v. Wausau Bus. Ins. Co., 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 5771, at *16 (N.D.Tex. Feb. 26, 2004); TIG Ins. Co. v. Dallas Basketball, Ltd., 129 S.W.3d 232, 238 (Tex. App.-Dallas 2004); Universal Underwriters Ins. Co. v. Lou Fusz Auto. Network, 300 F. Supp. 2d 888, 894-95 (E.D.Mo. 2004); Am. States. Ins. Co. v. Capital Assocs. of Jackson County, Inc., 2003 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 25532, at *19 (S.D.Ill. Dec. 9, 2003); Hooters of Augusta, Inc. v. Am. Global Ins. Co., 272 F. Supp. 2d 1365, 1373 (S.D.Ga. 2003); W. Rim Inv. Advisors, Inc. v. Gulf Ins. Co., 269 F. Supp. 2d 836, 847 (N.D.Tex 2003); Prime TV, LLC v. Travelers Ins. Co., 223 F. Supp. 2d 744, 752-53 (M.D.N.C. 2002).

[18] 59 F.3d 1541 (8th Cir. 1995). ����������������������������������������������������������������������

[19] Id. at 1548.

[20] These states include Florida, Kansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, and Texas.� See 1987 Fla. Laws ch. 253; Kan. Stat. Ann. � 50-670 (2005) (enacted in 1991); La. Rev. Stat. Ann. � 45:810 (2005) (enacted in 1991); Minn. Stat. � 325E.26 (2004) (enacted in 1987); N.M. Stat. � 57-12-22 (2005) (enacted in 1989); N.Y. Gen. Bus. Law � 399-p (2005) (enacted in 1988); Or. Rev. Stat. � 646.563 (2003) (enacted in 1989); Tenn. Code Ann. � 47-18-1501 (2004) (enacted in 1990).

[21] See Missouri Pac. Ry. Co. v. Larabee Flour Mills Corp., 211 U.S. 612 (1908); Southern Ry. Co. v. Reid, 222 U.S. 424, 425 (1911).

[22] 211 U.S. 612 at 621.

[23] Id.

[24] 222 U.S. 424 at 434.

[25] See Jones v. Rath Packing Co., 430 U.S. 519 (1977); Cal. v. ARC America Corp., 490 U.S. 93, 94 (1989).

[26] 430 U.S. at 525 (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 U.S. 218, 230 (1947)).

[27] 490 U.S. at 101; Smiley v. Citibank, 900 P.2d 690, 696 (Cal. 1995).

[28] 490 U.S. at 94-95.

[29] 467 U.S. 837 (1984).

[30] FCC Report and Order, In the Matter of Rules and Regulations Implementing the Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991 50 (adopted June 26, 2003, released July 3, 2003) [hereinafter FCC Report and Order].

[31] Id.

[32] Id.

[33] Id. at 50-51.

[34] Id. at 51, footnote 268.

[35] 137 Cong. Rec. S18317 (1991).

[36] Id.

[37] FCC Report and Order, supra, at 5.

[38] DMNews is an online newspaper for direct marketers.� DMNews Home Page, http://www.dmnews.com.

[39] Scott Hovanyetz, Emergency Triggers Louisiana Telemarketing Ban, DMNews, July 7, 2005.

[40] Hillsborough County v. Automated Med. Labs., 471 U.S. 707, 716 (1985) (there is a "presumption that state and local regulation of health and safety matters can constitutionally coexist with federal regulation.").

[41] See, e.g., Hill v. Colo., 530 U.S. 703 (2000) (upholding a law protecting the privacy and autonomy of individuals seeking medical care, as the law was intended to serve the "traditional exercise of the States' police power to protect the health and safety of their citizens.") (internal quotation marks omitted).

[42] FCC Report and Order, supra, at 46.

[43] 18 U.S.C. � 2710(f) (2005).�

[44] 12 U.S.C. � 3401 (2005).� While the Right to Financial Privacy Act does not contain explicit provisions regarding its effect on state law, the legislative history of the Act indicates that Congress intended to regulate access to customer records by federal agencies and departments only, without precluding states from regulating access of state and local agencies to such records.�

[45] 47 U.S.C. � 551(g) (2005).

[46] 18 U.S.C. � 2710(f) (2005).

[47] 29 U.S.C. � 2009 (2005).

[48] 18 U.S.C. � 2721 (2005).

[49] 29 U.S.C. � 1191 (2005).

[50] 15 U.S.C. � 6701 (2005).

[51] 15 U.S.C. � 1681t (2005).

[52] New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262, 311 (Brandeis, J., dissenting).

[53] The Privacy Protection Study Commission was created by the Privacy Act of 1974.� Privacy Act of 1974, Pub. L. 93-579 � 5, 88 Stat. 1896 (codified as amended at 5 U.S.C. � 552(a)).

[54] Privacy Protection Study Commission, Personal Privacy in an Information Society (1977), available at http://www.epic.org/privacy/ppsc1977report/.

[55] Id. at Appendix 1, Preface.

[56] FCC Report and Order, supra, at 11.

[57] FCC Report and Order, supra, at 46.

[58] The National Association of Attorneys General Privacy Subcommittee, Privacy Principles and Background, available at http://www.naag.org/naag/resolutions/subreport.php.�

[59] See e.g., State of Indiana's Reply Comments, In the Matter of Consumer Bankers Ass'n 5, CG Docket No. 02-278.

[60] Kristen Bremner, Acxiom Debuts Segmentation, Credit Tools, DMNews, June 29, 2005, at http://www.dmnews.com/cgi-bin/artprevbot.cgi?article_id=33220&dest=article.

[61] Claritas, Segmentation Analysis, available at http://www.clusterbigip1.claritas.com/claritas/Default.jsp?main=3&submenu=seg&subcat=segpirzmne (last visited July 2, 2005).

[62] Claritas advertisement, available at http://www.clusterbigip1.claritas.com/claritas/pdf/articles/Claritas_STORES_Aug_2004.pdf (last visited July 6, 2005).

[63] See Claritas advertisement, available at http://www.clusterbigip1.claritas.com/claritas/pdf/articles/Claritas_STORES_Aug_2004.pdf.

[64] See, e.g., State of Indiana's Reply Comments, In the Matter of Consumer Bankers Ass'n 4, CG Docket No. 02-278.